Why Japanese Feels the Need to Have 3 Entirely Different Writing Styles

The dreaded question when you begin learning Japanese:

The first thing you need to know, out of the three writing styles, two of them are alphabets. All three function separately, and have different "jobs" within the language. To demonstrate this, I will be referring to these simple sentences:

Now, with that established, let's talk about writing style number 1: Hiragana:

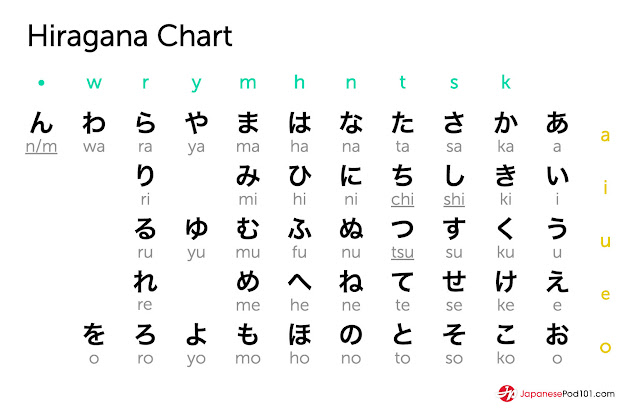

The chart above is all the characters in the modern hiragana alphabet. Each symbol represents a sound or syllable. so, Apple (ringo), would be spelled 「りんご」. The sound shifts aren't present on this chart, but by adding " or ° to a symbol, a sound shift occurs. In this case, こ (ko) is changed to ご (go). This is similar to the sound shift that occurs in English such as changing "knife" to "knives". the soft "f" is changed to the harder "v" sound.

Hiragana is used for many things, such as for grammar (like function words or particles), native Japanese words, or furigana. It's the "catch-all" of the two alphabets. So in our example sentences, the hiragana will be highlighted in red:

Next, is katakana, the second writing style, and the other alphabet:

There are two things you should notice right off the bat: they are all very angular looking, and these symbols represent the same sounds found in hiragana. So why the hell is there a second, suspiciously angular, alphabet for the same characters? Their functions are different.

Katakana's original purpose was to be a phonetic alphabet to help make borrowed words from other languages easier to say for Japanese people. Essentially, it's the alphabet that signifies that the word is foreign or borrowed. If English had this, EVERYTHING would be written in katakana it seems like. Some are simple translations such as "Arizona", which is just written as アリゾナ (a-ri-zo-na). However, words like "Taxi" are a little harder to recognize phonetically: タクシー (ta-ku-shii). Foreign words are adapted from all over the world, so even English speakers might now understand katakana words like パン (pan), the Italian word for "bread", and アルバイト (arubaito), coming from the German word for "job", arbeit.

Katakana has other usages such as for onomatopoeias and more modern ones like for making any word (native or not) stand out in advertising or making something look "hip". In our example sentences, katakana will be marked in green:

The final writing style is Kanji, you know, the pretty one that everyone gets tattooed:

Long story short, when the Chinese "discovered" Japan, the indigenous people ended up borrowing Chinese characters and adding their own pronunciations, giving the Japanese "kanji". These are only a few ... trust me. Unlike hiragana and katakana, kanji isn't an alphabet, they are full words. Kanji can be written out in hiragana and isn't uncommon. Learning kanji is like when you expand your vocabulary, neverending (or close to it). Also, notice that the Japanese only have a fixed set of phonetic sounds, therefore the word かみ (kami) can mean God, paper, or hair depending on how you write it out in Kanji.

To compare to English, only writing a word かみ, for example, is like only saying "there" in English. Do you mean "there", "their", or "they're"? Only writing かみ is like asking that; are you saying:"paper", "God", or "hair"? Therefore writing the kanji either "神", "髪", or "紙" is like writing out which "there" you are referring to. Kanji helps specify words in the language.

Kanji is primarily used for nouns and is NOT grammatical except for the root forms of verbs (when the verb is derived from an existing noun). In the case of verbs, Kanji has nothing to do with tense, politeness, etc., that is left to the hiragana on the "tail" of the verb. For example, 来る (to come) has both Kanji and hiragana counterparts and can be seen in our example sentences. Now to refer to said sentences, kanji will be purple:

From our sentences, 私 (watashi) means "I" and is normally followed by the subject marker は (wa), like in sentence two. However, the subject of sentence one is "my name" meaning that the subject marker comes after the phrase 私の名前 (watashi no namae). The の after 私 signifies possession, meaning that the name is mine. The hiragana works to connect the content words grammatically in these sentences.

An important note is that Japanese follows the SOV syntax order, unlike the English's SVO. So after the subject "my name" in sentence 1, comes my name マリー then the verb to be ("is" in this case) です. It reads more like 'My name Mary is', but you can see how it all comes together. Sentence 2 follows a similar pattern, except the subject is just "I" so it is just written 私は. The sentence's verb phrase "アリゾナから来ました" is literally backward to how you'd say it in English; 'Arizona from came' instead of 'came from Arizona', adding から after Arizona denotes that something is from Arizona. 来ました stems from the root verb 来る and is conjugated into the present tense as 来ます. Notice that the kanji never changes, just the hiragana attached to it. change the hiragana ます to ました, like in our sentence, and the verb becomes (positive) past tense.

I apologize for the grammar speak! But it is necessary in order to help answer the question of "why does Japanese have three unique writing styles in their language?". While the example sentences are very basic, they can easily relay how important each style is the grammar and overall function of the language. When learning Japanese, understanding this concept alone is vital to picking apart sentences for context clues and understanding where words start and stop. Just recognizing the styles (even if you haven't learned every symbol yet) helps you immensely in your own studies. For those not learning Japanese or planning to, I hope you learned something new!

~Maryちゃん

"B-but Sensei!!! Why are there sooo many different writing styles?? There are even TWO versions of the alphabet!"It's scary at first. You spend the whole first year learning the first two, hiragana and katakana and then get stuck with kanji, the one you literally never stop learning. So why are there three of them and why are they all important? Tofugu put out their "ultimate guides" to hiragana and katakana, which are more complete than my post, but I intend to summarize and add a bit of insight on how these writing styles, along with kanji work together in Japanese grammar.

The first thing you need to know, out of the three writing styles, two of them are alphabets. All three function separately, and have different "jobs" within the language. To demonstrate this, I will be referring to these simple sentences:

私の名前はマリーです。私はアリゾナから来ました。

My name is Mary. I am from (lit. come from) Arizona.

Now, with that established, let's talk about writing style number 1: Hiragana:

The chart above is all the characters in the modern hiragana alphabet. Each symbol represents a sound or syllable. so, Apple (ringo), would be spelled 「りんご」. The sound shifts aren't present on this chart, but by adding " or ° to a symbol, a sound shift occurs. In this case, こ (ko) is changed to ご (go). This is similar to the sound shift that occurs in English such as changing "knife" to "knives". the soft "f" is changed to the harder "v" sound.

Hiragana is used for many things, such as for grammar (like function words or particles), native Japanese words, or furigana. It's the "catch-all" of the two alphabets. So in our example sentences, the hiragana will be highlighted in red:

私の名前はマリーです。私はアリゾナから来ました。

My name is Mary. I am from (lit. come from) Arizona.In these sentences, hiragana is being used only for grammatical purposes such as to signify possession, the preposition "from", and to tense the verb "来ます".

Next, is katakana, the second writing style, and the other alphabet:

There are two things you should notice right off the bat: they are all very angular looking, and these symbols represent the same sounds found in hiragana. So why the hell is there a second, suspiciously angular, alphabet for the same characters? Their functions are different.

Katakana's original purpose was to be a phonetic alphabet to help make borrowed words from other languages easier to say for Japanese people. Essentially, it's the alphabet that signifies that the word is foreign or borrowed. If English had this, EVERYTHING would be written in katakana it seems like. Some are simple translations such as "Arizona", which is just written as アリゾナ (a-ri-zo-na). However, words like "Taxi" are a little harder to recognize phonetically: タクシー (ta-ku-shii). Foreign words are adapted from all over the world, so even English speakers might now understand katakana words like パン (pan), the Italian word for "bread", and アルバイト (arubaito), coming from the German word for "job", arbeit.

Katakana has other usages such as for onomatopoeias and more modern ones like for making any word (native or not) stand out in advertising or making something look "hip". In our example sentences, katakana will be marked in green:

私の名前はマリーです。私はアリゾナから来ました。

My name is Mary. I am from (lit. come from) Arizona.Our example sentences only use the more conventional side of katakana, translating foreign words such as my name and the name of my state phonetically.

The final writing style is Kanji, you know, the pretty one that everyone gets tattooed:

Long story short, when the Chinese "discovered" Japan, the indigenous people ended up borrowing Chinese characters and adding their own pronunciations, giving the Japanese "kanji". These are only a few ... trust me. Unlike hiragana and katakana, kanji isn't an alphabet, they are full words. Kanji can be written out in hiragana and isn't uncommon. Learning kanji is like when you expand your vocabulary, neverending (or close to it). Also, notice that the Japanese only have a fixed set of phonetic sounds, therefore the word かみ (kami) can mean God, paper, or hair depending on how you write it out in Kanji.

To compare to English, only writing a word かみ, for example, is like only saying "there" in English. Do you mean "there", "their", or "they're"? Only writing かみ is like asking that; are you saying:"paper", "God", or "hair"? Therefore writing the kanji either "神", "髪", or "紙" is like writing out which "there" you are referring to. Kanji helps specify words in the language.

Kanji is primarily used for nouns and is NOT grammatical except for the root forms of verbs (when the verb is derived from an existing noun). In the case of verbs, Kanji has nothing to do with tense, politeness, etc., that is left to the hiragana on the "tail" of the verb. For example, 来る (to come) has both Kanji and hiragana counterparts and can be seen in our example sentences. Now to refer to said sentences, kanji will be purple:

私の名前はマリーです。私はアリゾナから来ました。

My name is Mary. I am from (lit. come from) Arizona.Now that we know what each one is used for, how do they work together?

From our sentences, 私 (watashi) means "I" and is normally followed by the subject marker は (wa), like in sentence two. However, the subject of sentence one is "my name" meaning that the subject marker comes after the phrase 私の名前 (watashi no namae). The の after 私 signifies possession, meaning that the name is mine. The hiragana works to connect the content words grammatically in these sentences.

An important note is that Japanese follows the SOV syntax order, unlike the English's SVO. So after the subject "my name" in sentence 1, comes my name マリー then the verb to be ("is" in this case) です. It reads more like 'My name Mary is', but you can see how it all comes together. Sentence 2 follows a similar pattern, except the subject is just "I" so it is just written 私は. The sentence's verb phrase "アリゾナから来ました" is literally backward to how you'd say it in English; 'Arizona from came' instead of 'came from Arizona', adding から after Arizona denotes that something is from Arizona. 来ました stems from the root verb 来る and is conjugated into the present tense as 来ます. Notice that the kanji never changes, just the hiragana attached to it. change the hiragana ます to ました, like in our sentence, and the verb becomes (positive) past tense.

I apologize for the grammar speak! But it is necessary in order to help answer the question of "why does Japanese have three unique writing styles in their language?". While the example sentences are very basic, they can easily relay how important each style is the grammar and overall function of the language. When learning Japanese, understanding this concept alone is vital to picking apart sentences for context clues and understanding where words start and stop. Just recognizing the styles (even if you haven't learned every symbol yet) helps you immensely in your own studies. For those not learning Japanese or planning to, I hope you learned something new!

~Maryちゃん

Your enthusiasm and understanding of these different systems for the Japanese language is apparent in this post. Good job.

ReplyDelete